French and Indian War

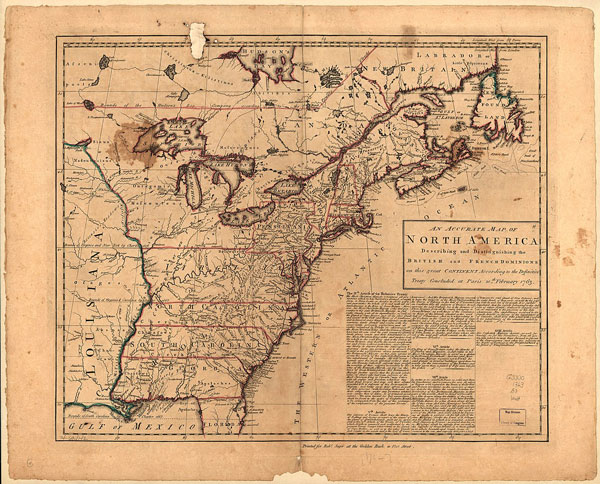

The French and Indian War started as a struggle for who would control the land west of the Allegheny Mountains in the Ohio River Valley. As the conflict spread European powers began to fight in their colonies throughout the world. It became a war fought on four continents.

Learn

Learn About the Past

“The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of American set the world on fire”

Horace Walpole’s comment on George Washington and the first shots of the French and Indian War as found in Robert C. Alberts, A Charming Field for an Encounter, (Washington, 1975) 20, was actually written by 19th century American historian Francis Parkman. Parkman “invented” the Walpole quote, as an exhaustive search of Walpole’s correspondence indicates.

From the 1750’s and through the early 1760’s, the British, the French, and many American Indian nations engaged in a war that changed the course of American history: the French and Indian War. It started over who would control the Ohio River Valley and a familiar figure, George Washington, was an early participant.

At the time about 3,000 to 4,000 American Indians were living in the Ohio River Valley. The French had settlements in Canada, the “Illinois country” and Louisiana (which included New Orleans). The British settled east of the Allegheny Mountains along the eastern seaboard. Both the French and the British thought they had an indisputable claim to the Ohio River Valley, as did the Indians who lived there. For both economic and political reasons all three powers wanted to control this region. As tensions and actions escalated a clash seemed inevitable. On May 28, 1754 the first shot was fired and as 19th century American historian Francis Parkman wrote, it “set the world on fire.”

Eventually France and Britain declared war on each other and the fighting spread from North America to Europe, the Caribbean, India, and the Philippines. War was not new to these powerful European nations. They had been traditional rivals and enemies in a dozen previous wars.

As the French and Indian War continued in North America the American Indians fought for their own cause. They were influential in shaping the outcome of the war.

The fall of the French colonial city of Montreal in 1760 signaled the end of fighting between the French and British on this continent. Those two powers agreed Britain would control the Ohio River Valley. However, the British did not keep their promises to the American Indians and instituted new unfavorable trade policies. These actions sparked Pontiac’s War in 1763. The British and American Indians continued to struggle over the land. Eventually the British won and settlers pushed most of the Indians westward.

At the end of the French and Indian War Great Britain had a vast new empire to administer. The relationship between the British colonies in North America and their mother country began to change. The British government enacted policies that set the stage for the American Revolution.

Who

Who Were the People Involved?

Shawnee, Seneca and Delaware Indian Nations

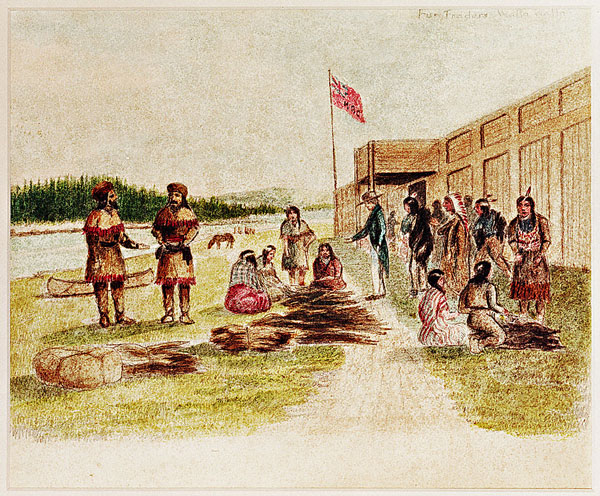

In the 1750s, the area west of the Allegheny Mountains was a vast forest. American Indians primarily from three nations, the Seneca, the Lenape (LEN-ah-pee) or Delaware, and the Shawnee inhabited the Ohio River Valley. There were about 3,000 to 4,000 American Indians living there. Their economy was based upon hunting, fishing and agriculture. With enough land they were self-sufficient. They hunted beaver and other animals for trade. A few French and British traders traveled through the area. The American Indians traded furs and food for metal products, cloth, firearms and other products. The American Indians were excellent warriors and scouts. During battles in the French and Indian War their presence often made the difference between winning and losing.

The Iroquois Confederacy

Land north of the Ohio River Valley, in what is now western New York was home to the Haudenosaunee (hou-DE-noh-sah-nee) or Iroquois Confederacy. To form the confederacy six nations had come together to coordinate their actions, policy and trade. The confederacy was extremely powerful and often controlled neighboring nations. The Seneca in the Ohio River Valley were members of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Lenape and the Shawnee were under their authority and representatives were sent from the Iroquois Confederacy to govern them.

Great Lakes Indian Nations

Beyond the Ohio River Valley were the nations around the Great Lakes. These nations were traditionally French allies. The French called these nations the “far Indians” and would often call on these warriors to assist them in defending their colony. The French also relied on the American Indian nations along the St. Lawrence River for assistance.

The population of all the Indian nations in northeastern North America was about 175,000.

The French

New France had three colonies: Canada (along the St. Lawrence River), the Illinois Country (the mid-Mississippi Valley), and Louisiana (New Orleans and west of the Mississippi). There were about 70,000 colonists throughout the French settlements. Their economy was based on trade with the American Indians. It was a weak economic system and the colonies were not self-sustaining. They needed to purchase food from the Indians or import it. The French colonists had a much different relationship with the American Indians than the British. They viewed the American Indians as trade partners and established personal relationships with the nations they traded with. They became members of the native communities and often inter-married and had children. Rivers and waterways were the best means of transportation through the interior of the continent. The French had a series of forts and trading posts along the main travel and trading route, west of the Ohio River Valley. The Ohio River Valley was an alternate transportation route. Even though the French did not have trading posts or settlements in the Ohio River Valley, they claimed the land as theirs.

The British and Her American Colonies

To the east of the Allegheny Mountains lived more than 1.2 million people in 13 British colonies, nearly a quarter of whom were slaves or indentured servants. Their economies were growing and diverse, ranging from a strong mercantile shipping trade with Great Britain and her Caribbean colonies to mixed agriculture, small businesses, fishing, and thriving tobacco, rice, and sugar plantations in the South. Slave and indentured labor sustained much of this economic growth. The population was also expanding rapidly, growing to nearly 1.5 million by 1775. Although there were no settlers in the Ohio River Valley in 1750, the British colonies claimed the land. Virginia, in fact, laid claim to all the lands as far west as the “islands of California.”

Although their economy did not depend on it many Pennsylvania and Virginia traders were traveling to the Ohio River Valley to trade. They did not have river access to the valley and there were no roads for wagons. To get their goods across the mountains they used packhorses.

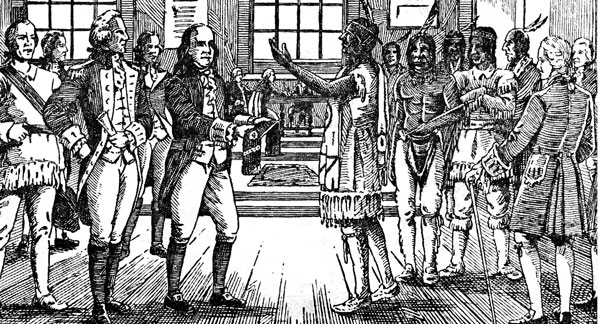

The British colonists generally did not mix with the American Indian societies. However, the two cultures needed to deal with each other. They needed people who could interpret the languages and also understand the different cultural customs and manners. The people who did this were called “Go Betweens.” They were more than translators; they were also diplomats.

What

What Were They Fighting For?

Fur Trade

The Ohio River Valley Indians wanted to maintain their land, their lifestyle, and control of their future. They sought to trade with the Europeans but prevent settlement. By this time the American Indians were dependent on European goods. Guns, gunpowder, knives, lead for musket balls, rum and cloth were a few of the items they did not want to live without. They were excellent hunters and were able to kill the game and beavers the Europeans sought. Most of the Shawnee and Lenape living in the Ohio River Valley had only started living there in the 1720s. They had moved to the region from their homes in eastern Pennsylvania. As the British colonists settled that land the American Indians moved west. The Shawnee and the Lenape also did not like being under the control of the Iroquois Confederacy. They wanted to speak for themselves. The Iroquois Confederacy wanted to maintain control of the Ohio River Valley so that it was in a better negotiating position with the French and British.

Transportation Access

The French depended on the Indian trade as the basis of their economy. They were upset when Pennsylvania and Virginia started trading with the Ohio River Valley Indians. This area was on the eastern edge of their main trading routes and they did not want to lose control of any of the trade. Also they used the Ohio River Valley and its river systems as a transportation route. They wanted their traders, priests, and soldiers to be able to travel freely through the region. The French were not interested in settling the area. However, they were determined to maintain authority over it.

Land

The British colonial settlement had reached the eastern base of the Allegheny Mountains. They saw wealth and opportunity in the vast lands west of the mountains. Wealthy colonists sought land grants in the hopes of securing lands that they would sell to settlers at a profit – land speculation. There were many settlers seeking to own their own property. However, to get land speculation profits they needed more farmland and the Ohio River Valley looked like a perfect place to get it. The British colonial traders involved with Indian fur trade were already making fortunes. None of these colonists wanted to see the French control the Ohio River Valley. The British saw many opportunities and they did not intend to lose them to their enemies, the French.

The goals and economies of the three nations also impacted how they viewed and interacted with each other. The British emphasis on farming and owning land often put them in competition with the American Indians. The French were more likely to view the American Indians as allies since their economy depended so heavily on American Indian trade. The preservation of trade was important to the American Indian nations and often influenced which alliances they made.

Beginning

How Did the Conflict Begin?

The Celeron Expedition

In 1749 the French were becoming concerned with the Pennsylvania and Virginia traders in the Ohio River Valley. That summer they sent an expedition of 230 armed men under the command of Captain Pierre-Joseph Celoron (SEL-or-ohn) de Blainville down the Ohio River. Celoron buried lead plates in the ground stating the French claim to the land. He made speeches to the Ohio River Valley Indians warning them not to trade with the British and expelled the traders he found. In Logstown (near present day Ambridge, PA) he found 10 British traders with 50 packhorses and 150 packs of fur. When he returned to Canada he had a bleak report. The Ohio River Valley Indians “are very badly disposed towards the French.” In order to keep the valley he recommended that the French build a fortified military route through the area.

The French Build Forts

In 1752, the Marquis Duquesne (dyoo-KAYN) was named Governor of Canada. His instructions were “to make every possible effort to drive the English from our lands . . . and to prevent their coming there to trade.” The next year he began building a series of forts along the waterways in the Ohio River Valley. These forts were at Presque Isle (presk eyel), on the south shore of Lake Erie and Fort LeBoeuf (luh-BOOF) on French Creek, a tributary of the Allegheny River.

Washington Warns the French to Leave 1753

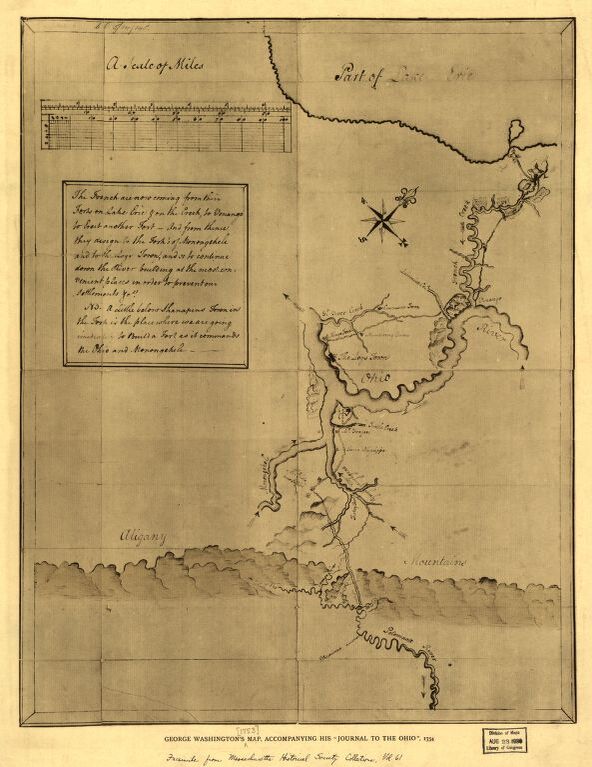

Meanwhile, Robert Dinwiddie (DIN-wid-dee), the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, was granting land in the Ohio River Valley to citizens of his colony. In 1753, he received instructions from the King of England “for erecting forts within the king’s own territory.” Dinwiddie was very upset about all the French activity in the Ohio River Valley. He sent a young volunteer, George Washington, to deliver a letter to the French demanding that they leave the region.

Not surprisingly, the French refused to leave. While Washington made the arduous 900 mile winter trip from Williamsburg to Fort LeBoeuf (present-day Waterford, PA) and back again, he noted in his journal on November 22, 1753 “As I got down before the Canoe, I spent some Time in viewing the Rivers, & the Land in the Fork, which I think extreamly well situated for a Fort; as it has the absolute Command of both Rivers.” He was referring to the point of land at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, called the “Forks of the Ohio,” which is now the City of Pittsburgh, PA.

The French Take the Forks of the Ohio 1754

In the spring of 1754 the French finished Fort Machault (mah-SHOH), near where French Creek and the Allegheny met (present-day Franklin, PA). At the same time the British started to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. They had just hung the gate when at least 500 French troops, along with many cannon, appeared. The British commander, Ensign Edward Ward, quickly realized that he was badly outnumbered. He and his soldiers left the fort to the French, who began building a much stronger fortification that they named Fort Duquesne.

Many of the Ohio River Valley Indians were concerned with the large number of troops and their fort building activities. Since the British traders had been forced to leave, the Indians in the region now traded with the French. They found the French trade goods to be more expensive and of a poorer quality than the British.

The British React

Later the same year, Washington was sent to the Ohio River Valley with the Virginia militia. He and his troops were told to take the “Lands on the Ohio; & the Waters thereof.” Their orders specified that they were to widen the packhorse trail into a road wide enough for wagons. While at Will’s Creek (what is today Cumberland, MD) Washington learned that the French were in control of the Forks of the Ohio and the fort the British had built there. Washington proceeded forward with the construction of a road across the mountains. The British hoped to use this road to re-take control of the Ohio River Valley.

Over 50 miles west of Will’s Creek Washington stopped to rest his men and horses in an open meadow called the Great Meadows. While camped in the meadow Washington received a message from Tanaghrisson (tan-ah-gris-suhn). Tanaghrisson was a Seneca sent by the Iroquois Confederacy to govern over the Lenape in the Ohio River Valley. His position was given the title the Half King. The Half King sided with the British and his message told Washington that there was a band of French soldiers nearby. On the night of May 27, 1754 Washington and 40 soldiers marched through a dark and wet night. It was morning before they arrived at the Half King’s camp. Together they decided to surround the French.

Battle of Jumonville Glen 1754

Unaware, the French under the command of Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville (joo-mon-veel) were just getting up when a sentry spotted Washington’s men. A recently discovered account suggests that George Washington fired the first shot, followed by a volley from his men. The French, unprepared and in a bad position at the bottom of the ravine, attempted to escape, but met the Half King and his warriors, forcing them to surrender.

The whole skirmish lasted only 15 minutes. One French soldier escaped and 21 were captured. Jumonville lay wounded and 12 others were dead. The Half King approached the wounded Jumonville and said “Thou are not yet dead my father.” Then he raised his tomahawk and killed him. It was both a horrifying and symbolic gesture, for to the Half King and his people, the French were not welcome in the Ohio Valley. What both Washington and the Half King could not recognize, however, was that once the news of the “murder” of Jumonville reached the French court of King Louis XV, it created a global diplomatic uproar, for the French maintained that Ensign Jumonville was on a peaceful diplomatic mission to warn the British to leave the region. As American historian Francis Parkman would write a century later, “The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire.”

Fort Necessity 1754

This skirmish invited retaliation from the French and their American Indian allies. Washington returned to the Great Meadows where his troops built a small fort they named Fort Necessity. Washington received more troops bringing the total number of British to nearly 400.

On July 3, 1754 about 600 French and 100 of their American Indian allies arrived in the Great Meadows just beyond Washington’s fort. Jumonville’s brother Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers (deh VIL-yay) commanded the French army. They quickly found a weakness in the fort. In one area the trees were within firing range of the fort. The French and their allies concentrated their troops behind these trees. Then the weather turned against the British. It began to rain. The gunpowder that fired the muskets would not ignite. As night approached British were in a bad position. They had been fighting all day and there were many dead and wounded. About 8:00 in the evening the French called and asked if they would like to negotiate a surrender. Realizing their poor situation the British agreed to negotiate.

Washington sent Captain Jacob Van Braam to negotiate. Although he was a Dutchman he spoke French and English. After 4 hours the final surrender document was ready and Washington signed it. There were many provisions. One provision Washington claimed had been translated as the British being responsible for the death of Jumonville. Later Washington learned that the document, which was written in French, actually twice mentions the assassination of Jumonville. This was a surprise and a humiliation for Washington. It also gave the French a document pinning the blame for the fighting on the British.

When Washington and his troops departed, the French again controlled the land west of the Allegheny Mountains.

The Ohio River Valley Indians who felt more comfortable dealing with the British than the French moved from the area. Many of them moved east to central Pennsylvania.

Braddock’s Expedition 1755

Although officially not at war both France and Britain supported the fighting by sending troops and supplies. Early the next year, Major General Edward Braddock arrived to take command of all the British forces in North America. Braddock invited George Washington to join him as a volunteer. Washington eagerly accepted and went along as his aide. Braddock would personally command the troops that set out to capture the Forks of the Ohio. They would march to Will’s Creek, where over the winter Fort Cumberland had been built. From there they would cut a road through the forested mountains to Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio.

“Braddock had trouble from the start locating horses and wagons to move the supplies for his army. Luckily for him, Benjamin Franklin and his son William came to the rescue. Acting as agents for the Colony of Pennsylvania, and risking some of their own funds, both men successfully negotiated the rent of over 150 wagons, 259 pack horses, and their drivers, which joined Braddock’s army in time to save the campaign.

By the time they reached Fort Cumberland, the British were well behind schedule. While preparing at Fort Cumberland, Braddock managed to anger and alienate almost all of the American Indians who came to participate as allies. Shingas (SHING-as), the leader of the Ohio River Valley Lenape was so angry he left and immediately joined the French. Scarouady (scar-roh-ah-dee) and seven other American Indians were the only ones who assisted the British. The 2,400 troops began leaving Fort Cumberland May 29, 1755.

The uncut forests and mountainous terrain of western Maryland and Pennsylvania proved more challenging than Braddock had anticipated, and fearing further delays, he agreed to George Washington’s suggestion to divide his army and form a “flying column” of 1300 soldiers who would move ahead more swiftly without all the heavy artillery and baggage, which would come up behind as quickly as possibleThe French at Fort Duquesne were well informed by their American Indian scouts of Braddock’s progress. There were hundreds of Indians around Fort Duquesne, but they thought Braddock’s army was too large and were unwilling to join the French.

On the morning of July 9 Captain Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Lienard de Beaujeu (Bo-joh) did the impossible. He convinced the American Indians to join the French. That morning 254 French and 637 Indians left Fort Duquesne.

Eight miles east of the Fort the French and British armies spotted each other. Contrary to legend, the British were not “surprised”—as they were fully expecting a possible attack, and in the opening phases of the battle, Captain Beaujeu was killed and some of the French Canadian militia began to scatter. While Braddock’s forces won the first phase of the battle, the French rallied and their American Indian allies took the initiative, seized the high ground, and attacked along the flanks of the British forces in a half-moon formation. The result was a British defeat, with two-thirds of the men and most of the officers killed or wounded, including General Braddock. George Washington, who narrowly escaped death, organized the retreat back to the camp of Colonel Thomas Dunbar, Braddock’s second in command, some 50 miles away. Four days later, General Braddock died of his wounds, and his body was buried in the road to prevent its discovery.

As a result of Braddock’s defeat many Ohio River Valley Indians decided to side with the French. For the next few years Fort Duquesne became the starting point for hundreds of French and Indian raids of the Pennsylvania and Virginia frontier.

Progress

How did the War Progress?

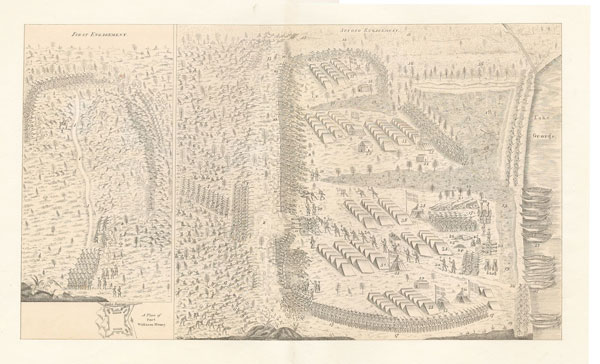

Battle of Lake George 1755

Despite the many setbacks, there was some glimmer of hope for the British. In September 1755 British forces led by Indian agent Sir William Johnson beat the French at the Battle of Lake George in northern New York and captured their commander. Johnson, with 1500 colonial troops and a number of Mowhawk warriors defeated an equal number of French and allied Indians led by the Baron de Dieskau. After the successful battle, Johnson consolidated his territorial gain by building Fort William Henry.

Britain Officially Declares War 1756

It was not until May 1756, that Britain officially declared war on France and the two countries began fighting in Europe. French and British colonies in the West Indies, India, and Africa were also drawn into the conflict. In Europe the war became known as the Seven Years War.

That same year both French and British colonies got new commanders. The British commander-in-chief, Lord Loudoun, did not understand the American colonists. When he made requests of colonial governors they sent the requests through their assemblies. Often the assemblies did not comply and Lord Loudoun would threaten to use force against the colonies. Some colonists started to see Lord Loudoun as being as much of a threat to their freedom as the French and American Indians. Lord Loudon’s actions created resentment and resistance. Resentment to his policies did not help the British war effort.

The new commander of the French colonies, Major General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (mon-KALHM) arrived in Canada in May of 1756. He was reluctant to use the American Indians to their full advantage and was disdainful of the Canadians. Although it took several years, his attitudes and actions eventually affected France’s success.

In 1756, the French continued to be victorious in North America. They used their American Indian allies successfully to defend their colony and to defeat the British at Fort Oswego.

The Battle of Kittanning 1756

The only British success that year was at Kittanning. Colonel John Armstrong led a party of 300 against the Lenape town of Kittanning. They surprised the town at dawn; however, the Indians put up a strong fight. They eventually set the town on fire. Lenape Chief “Captain” Jacobs was killed when the gunpowder stored in his house exploded after the house was set on fire. Armstrong left with 11 recovered captives and about a dozen scalps. The Pennsylvanians viewed this as a victory while the French and Ohio River Valley Indians saw it as a massacre. To avenge the attack the French and Indians intensified their raids on the Pennsylvania frontier.

Fort William Henry Massacre 1757

The French victory at Fort William Henry in 1757 ended in disaster for all. Montcalm had 1,800 American Indians with him. They fought with the French without pay in the hope of victory. They would get their compensation by taking captives, booty, and scalps. Many had traveled hundreds of miles to participate in the battle. When the British surrendered Fort William Henry Montcalm did not consult his Indian allies when he drew up the surrender terms. The surrender terms denied the warriors the plunder they had fought for. The day after the surrender the American Indians decided to take what they saw as their due and on August 10th captured or killed hundreds of British (mostly colonists). The American Indians unknowingly took captives and clothing infected with smallpox. That winter many nations suffered heavy losses due to the disease. The attack on the British colonists after the surrender intensified the colonists’ hate for the French and their Indian allies. Although the surrender was a victory for the French it was also a turning point. After the way the American Indians were treated by the French at Fort William Henry many of them decided not to fight with the French again. The French would never be able to ask for Indian assistance to the extent they had before. Loss of their American Indian allies was one of the factors that contributed to the tide of the war changing in favor of the British.

William Pitt Takes Charge 1758

In 1758, policy changes helped the British. William Pitt, Secretary of State in Britain, recalled Lord Loudoun and sent a new commander-in-chief. He repealed unpopular policies and enacted some that were very advantageous to the colonies. The colonies reacted with enthusiastic support of the war. For the first time colonial manpower and money was wholeheartedly put into the war. Pitt also sent many more troops to the colonies.

That year Pitt ordered a three-pronged attack on French strongholds. General Jeffery Amherst was to attack the fortress at Louisbourg, on the St. Lawrence River. General James Abercromby was assigned to take Fort Ticonderoga. General John Forbes was given the task of capturing Fort Duquesne.

In July Amherst captured Louisbourg, which opened the St. Lawrence River and a water route to Canada. Although not ordered in the plan Lieutenant Colonel Bradstreet also successfully captured Fort Frontenac. This fort supplied the goods and ships for the entire western French army and the important French trade with the American Indians. Bradstreet reported the French told him “that their troops to the southward and western garrisons will suffer greatly, if not entirely starve, for want of the provisions and vessels we have destroyed.” Abercromby did not take Fort Ticonderoga.

The Forbes Expedition 1758

Forbes believed in a strategy known as a “protected advance.” As the army moved forward, it would build forts or supply bases at regular intervals. He ordered construction of a new road across Pennsylvania, guarded by a chain of fortifications. The last fort built in September was to be the “Post at Loyalhanna,” Fort Ligonier, about 50 miles from Fort Duquesne. It would be a supply depot and a staging area for a British-American army of 5,000 troops.

On September 14th the British made a foolish attempt to capture Fort Duquesne and were defeated with many casualties. On October 12th the French attacked Loyalhanna (Fort Ligonier), but the British successfully defended their position. Washington arrived at Loyalhanna in late October.

While Forbes was moving forward, an important conference was taking place in Easton, PA. Representatives from the Iroquois Confederacy, the Shawnee and the Lenape met to make peace with the British. In return for not fighting with the French the British made several promises to the American Indians. The treaty they signed promised that the British would prevent settlement on all of the lands west of the Allegheny Mountains after the war. The British also committed to regulating the rum trade and eliminating forts on Indian lands. The Treaty of Easton was signed in October. “Go Betweens” brought news of the treaty to the Ohio River Valley Indian towns. This was bad news to the French.

It was so late in the fall that Forbes was considering ending the campaign for the winter. On November 12th, Washington captured a French soldier near Loyalhanna. The soldier told them that the French were very weak. Forbes decided to continue his campaign against Fort Duquesne. The French were in a bad position. They could no longer count on help from the American Indians and with the fall of Fort Frontenac they had very few supplies. They decided to abandon Fort Duquesne. The French destroyed the fort before they left. Forbes occupied the ruined fort on November 25th and renamed it Pittsbourgh in honor of the Prime Minister of England, William Pitt. Fort Pitt, as it was later named, became one of the largest English strongholds in North America.

Battle of Quebec 1759

In 1759, the British continued their success in battle. The Iroquois Confederacy, which had remained politically neutral until this point, decided to side with the British. During the summer the British captured Fort Niagara, Fort Ticonderoga, and Crown Point. The opening of the St. Lawrence River allowed the British to sail to Quebec. All summer British Major General James Wolfe was unsuccessful in attacking the city situated on the top of a cliff. Finally in September, under the cover of darkness Wolfe used a small footpath to get his troops up the cliff and onto a flat field outside the city. He probably learned of the footpath from Major Robert Stobo who was with him that summer. Stobo had been a prisoner in Quebec and had just recently escaped. Wolfe’s troops fought the French under the command of General Montcalm and won. The British took control of Quebec. Both generals died from wounds they received during the battle. The French colonial government moved to Montreal.

The Beginning of the End

The destruction of the French Fleet in November 1759 was the final blow for the French. Without supplies the French army could not retake Quebec. In 1760 the British captured Montreal. The war between France and England ended in North America.

End

How Did the Conflict End? What Were the Consequences?

Treaty of Paris 1763

After the fall of Montreal the warfare continued in other parts of the world. Spain entered the war when the British attacked and captured Havana, Cuba. The 1763 Treaty of Paris formally ended the war. France gave the British all of its land in North America east of the Mississippi River, other than the city of New Orleans. The French land west of the Mississippi, called Louisiana, was given to Spain. The Spanish gave Florida to Britain and the British returned Havana. There were several other small exchanges and agreements. The end result was that the French no longer had territory in North America.

In 1759 the British began construction of Fort Pitt on the site of the French Fort Duquesne. The American Indians became concerned. The Treaty of Easton promised to eliminate forts on American Indian land – yet this fort was much larger than a trading post. It was ten times larger than Fort Duquesne. The barracks could shelter hundreds of men. Lenape Chief Pisquetomen wanted to know what “ye General meant by coming here with a great army.”

With the French gone settlers began to move over the Allegheny Mountains. As always they saw opportunity for profit and advancement in the Ohio River Valley. It was becoming clear the promises of the Treaty of Easton were not to be honored.

Broken Promises and Bad Policies

In the fall of 1761 commander-in-chief Jeffery Amherst made some well-meaning, but ignorant changes to the British American Indian trade policies. The long-standing practice of gift giving was curtailed. Traders were forbidden from trading in the American Indian villages. This forced the Indians, who were often without horses, to carry their pelts into forts in small quantities. The traders were also required to limit the sale of lead and powder to five pounds at a time. This meant that the American Indians could not effectively carry out their fall and winter hunts, and thus were unable to provide for their families and towns. Additionally the new reform forbade the sale of rum and liquor to the Indians, a substance that had become part of their culture. These changes caused suffering and hardship in American Indian villages across the region. Many nations saw the benefits of allying with each other against their common enemy, the British, who were threatening their way of life.

Pontiac’s Rebellion 1763

In the spring of 1763 Pontiac, an Ottawa war chief, united warriors from many nations and on May 9th attacked Fort Detroit. American Indians had never before mounted a united and widespread attack on Europeans. The uprising spread. Within two months eight British forts fell, and Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt were isolated and under siege. Other frontier forts and settlements experienced persistent attacks and raids.

British commander Captain Simeon Ecuyer realized Fort Pitt was in a dangerous situation. Right before it was attacked two Lenape leaders came to the fort to negotiate. Ecuyer refused to surrender. When the chiefs departed he gave them gifts including two blankets and a handkerchief intentionally taken from the fort’s smallpox hospital.

Battle of Bushy Run 1763

British Colonel Henry Bouquet (BOO-kay) undertook an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt. On August 4, Bouquet left Fort Ligonier with packhorses carrying bags of flour as well as some other provisions. The next day American Indian warriors attacked them at Bushy Run. Bouquet’s troops suffered under fire from an unseen enemy and from thirst in the August sun. That night Bouquet, a commander who understood American Indian tactics, developed a clever plan. On the morning of August 6th, Bouquet’s troops pretended to be retreating. Instead, they circled around and attacked the warriors from another direction. Bouquet’s plan succeeded. He drove off the American Indians. Although one-quarter of his men were dead or wounded and he had lost all his flour, four days later Bouquet arrived at Fort Pitt. His arrival allowed Fort Pitt to be relieved.

Royal Proclamation of 1763

To settle the troubles with the American Indians, British policy makers in London decided to draw a line down the Allegheny Mountains. Everything between the mountains and the Mississippi River was reserved for the American Indians. There would be no settlements, only trading posts. Signed in October of 1763, the act was called the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The proclamation angered settlers who had fought for land in the Ohio River Valley. Although military leaders at Fort Pitt and other forts were aware of the Proclamation they rarely enforced it and settlers continued to flock to the area.

Pontiac’s War ended in 1765. The British changed their unfavorable trade policies with the American Indians. The Indians were ready to resume trade. The French had not joined in fighting the British as the American Indians had hoped. One of the conditions of peace at the end of Pontiac’s War was that the American Indians were required to return their British captives.

Consequences

The outcome of the French and Indian War affected all three powers. Before the French and Indian War, most wars between the old rivals France and Britain ended in a stalemate. The French and Indian War, however, had a decisive winner. Britain defeated France and became the most powerful European country. They now had a vast new empire to manage. The French were looking for an opportunity to revenge their defeat. The American Indians were faced with British rulers who were not going to stop the flow of settlers into the Ohio River Valley and other native lands. The Ohio River Valley Indians eventually lost their land. To keep their traditional lifestyle they moved further west.

Text courtesy of National Park Service educational kit “The French and Indian War.”